Employers can reduce the number of people dropping-out of vocational training by encouraging students to proactively seek help when they start struggling. Simple but effective communication with practical advice, sent at optimum times, is key.

The following post summarises my team’s recent report.

Summary

- Our partner is a government regulator of vocational education and training. They wanted to promote their support services to students who may be struggling to complete their apprenticeships and traineeships

- Our project tested SMS messages that significantly decreased dropout rates by 16%

- I trained our partner agency on how to implement this behavioural change, so that it became standard business practice

- SMS messages are most effective when they are personalised. They should make it easy to take action on the spot, such as applying for specific types of help at an optimum time that suits the customer

Background

Around 40% of students quit their apprenticeships and traineeships in New South Wales.

My team’s previous research established that students lack adequate support from their employers while they are undertaking an apprenticeship or traineeship. Employers sometimes lack the time, resources or skills to effectively supervise their apprentices and trainees.

When students struggle, they are overwhelmed, and don’t know where to turn to for support. Our research shows that a significant number of students drop out in their first year, and they rarely reach out for help before they do so.

I’ve spent the past year or so managing a scale-up project. That is, we took the findings of our randomised control trial that had proven effective in increasing support for students, and I then supported our partner agency to implement our results into ‘business-as-usual.’ The latter requires skilling up our partners to deliver the intervention on their own, without me running the day-to-day work. This is how we implemented this scaling.

What We Did

My team tested six behavioural SMS to support 13,065 first-year learners, as our previous research shows they are most at-risk of dropping out of training.

Learners were randomly allocated into three groups – two received the intervention, and the control group received no SMS. Each treatment group received a separate set of behaviourally informed messages. Each SMS had an URL link to an existing online resource on the Training Services NSW (TSNSW) website, plus an ongoing reminder to call their local office for support if they needed help. The two message themes of ‘Fair Go’ and ‘Incentives’ were chosen by TSNSW Executives and Regional Managers, because these have the highest strategic importance to their customers (learners).

Self-efficacy (Fair Go)

One-third of learners in our sample (n=4,288) received six SMS about a ‘Fair go.’ Our SMS messages prompted learners to reach out for help if they were at risk of cancelling due to immediate issues at work. We also encouraged learners to plan with links to practical tips and resources so they could better manage stressful situations during their training (planning fallacy). The six Fair Go messages told learners to:

- Expect to learn new skills and receive mentorship at work (self-efficacy)

- Complete their skills plan, due by May (timeliness)

- Reflect on their progression and act before they go off track (planning fallacy)

- Keep building their responsibilities and skills, with the help of their teachers, additional tutors, and their workplace supervisors (gain framing, goal setting)

- Stick to their training contract hours, so as not to impact their wellbeing and success (loss framing)

- Celebrate their hard work, and explore options to complete first year (reciprocity).

Incentives

One-third of our sample (n=4,223) received six SMS about Incentives. When people struggle, they will focus on smaller rewards they can get sooner (e.g. quitting their apprenticeship for another job that doesn’t require additional study), and they will forgo long-term opportunities (gaining a qualification in a few years, which will lead to a higher paying career in the long run) (hyperbolic discounting). We appealed to both intrinsic and extrinsic incentives, to encourage learners to stay in their contracts.

Intrinsic incentives are nonmonetary rewards that appeal to self-improvement. This can be effective in lifting attendance and enrolment.

Our messages were informed by TSNSW student surveys on what students seek assistance about and reasons given for contract cancellations. Extrinsic incentives can improve educational performance when linked to financial and material goals. Our Incentives messages highlighted financial subsidies, scholarships, and bonuses available to learners. We also prompted learners to consider the costs and benefits of progressing with their qualification.

The Incentives messages told learners to:

- Take advantage of travel concessions and other entitlements (extrinsic incentive)

- Succeed in training with available financial help (intrinsic incentive)

- Stay focused on progression, which leads to annual salary increases (hyperbolic discounting)

- Keep building on responsibilities and skills, as they may be eligible for penalty rates and other allowances (gain framing, goal setting)

- Work safely to enable success, financial benefits and promotion, and to seek early help when injured so they’re not left behind (loss framing)

- Celebrate their hard work, and the potential for early completion, which leads to higher pay or promotion (reciprocity, gain framing).

Control

One-third of our sample (n=4,554) received business-as-usual. That is, they did not receive any SMS, but they still have access to the same support and resources as the treatment groups (they can visit the website resources any time, or call their local office for help).

How We Did It

Our project used social science to make behavioural change easy. We ensured messages were attractive to students. Messages incorporated social influence. The SMS were also sent at optimum times.

Make it easy to act

We addressed information bias. Students are given a lot of information when they first sign up for an apprenticeship or traineeship, and they receive this from multiple organisations (their training organisation, and various government organisations). It can be overwhelming to sort what messages are important now versus later, and to recall this information at when we need it most.

We took an inventory of all the SMS messages already being sent to students, to establish themes, timing, frequency, and outcomes of these campaigns. We used these analytics to establish a messaging plan.

We reviewed existing data on what student feedback already exists, including complaints and reasons for contract cancellations. We also collated the various incentives offered by our partner that might interest students. For example, travel concessions.

We evaluated all the information provided to students when they first sign up for study, as well as other demographic data. We aligned this to our partner agency’s strategic plan and broader messaging. This helped us to create a list of key themes for our messages.

We worked with relevant experts within our partner agency to create a customer journey map, to identify key times when students might be most receptive to new information.

Our partner identified webpages that they wanted to include in each message. We used behavioural science to optimise these webpages for mobile phones. This includes reducing unnecessary detail (information bias), improving the layout, and ensuring the information and contact details on the webpages matched the relevant messages.

Ensure messages are attractive

We then used the key themes to co-design the SMS messages with executives and leaders from each region. This ensured we had stakeholder buy-in and endorsement from decision-makers, and that the messages aligned with their objectives.

Our messages highlighted incentives that appeal to both personal goals (intrinsic motivations, such as resilience), and broader rewards and benefits (external motivations, such as getting discounts and other perks).

We addressed salient bias. Our memory is affected by our senses and subjective experiences. Organisations often send people messages that are hard to complete on the run, such as filling in a cumbersome form or signing up to a new program with multiple steps. We experience this negatively and therefore do not action such messages. Behavioural science research shows that people are more likely to pay attention to, remember, and act on information that stands out.

We designed messages to be actionable on the spot. We included a call to action, such as getting reimbursement, with a link to a streamlined webpage that provided further information. Our messages also included a phone number and contact details to get more help.

We were able to track the actions people took, including clicking on the link, calling for help, messaging back, or opting out of future messages. We had a very low opt out rate.

Keep it social

We drew on social influences to encourage behaviour change. Each message contained simple language that clearly ensured students understand their workplace rights, set expectations, and encouraged students to take proactive steps when they started to struggle with their studies.

We personalised messages, by including the learner’s name, their qualification, and sign-off from their local training manager.

We included social norms to reinforce the students’ progress. We wanted to keep encouraging them throughout their first year.

We changed the default bias. When people struggle, they tend to do nothing, and go with the flow (default bias). This means problems compound, and students end up dropping out. Each message reinforced that change is possible. We gave clear examples about alternative options to help students reach their learning and career goals if they were struggling.

Make it timely

We ensured messages were timely. We used existing studies on the best time to message students, and tested which messages led to more students progressing with their qualifications.

We tested messages at optimised times, including during breaks and end of day (as apprentices and trainees sometimes work from 5.30am to 3.30pm). We found the best times to reach students was weekdays at 11am, 12pm, and 3pm. We timed each of the six campaigns around key moments in the learning journey. E.g. Signing the employer contract.

What We Found

We used a messaging platform to monitor:

- Message responses: these were sent to the relevant local manager to respond to

- Opt-outs: we benchmarked these to ensure they were well below the national average

- Call to action: we analysed the number of people clicking on the links in the SMS

- These actions were used to track the short-term outcomes of the message campaign.

During our trial, 552 learners proactively called their local office for help, usually within minutes of receiving our SMS. They would otherwise not have sought support, with issues snowballing, they may have potentially dropped out.

Additionally, over 500 learners responded to our SMS via text, seeking follow-up support.

The opt-out rate for the six campaigns (less than 2%) was half the rate than the national average (3.8%).

After 12 months, we checked the number of students who had dropped-out, to test our long-term outcomes, and ensure messages remain effective.

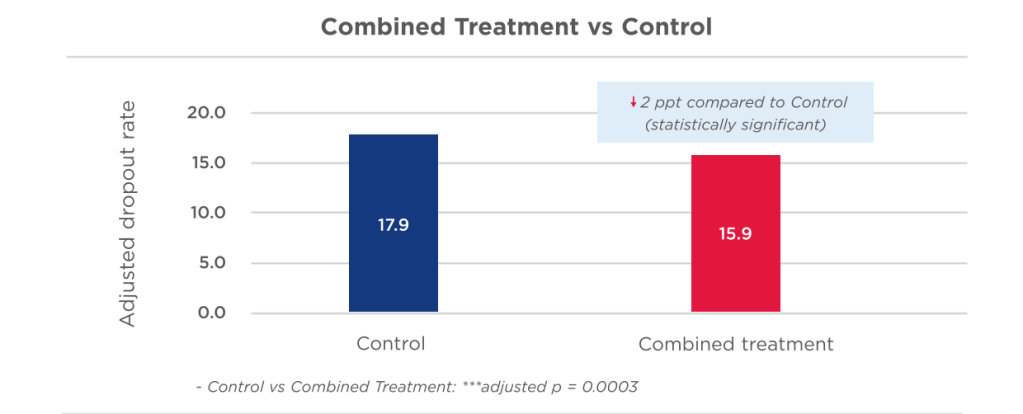

First, looking at whether students were still studying (whether on their first or subsequent

contract), we found that our behavioural SMS (regardless of which version learners received)

significantly reduced the drop-out rate by 2 percentage points (ppt) in comparison to learners

who did not receive a SMS. To put it another way, 18% of learners in the control group (who did not receive any message) had dropped out 12 months after our study, compared to 16% of those who received either of our messages.

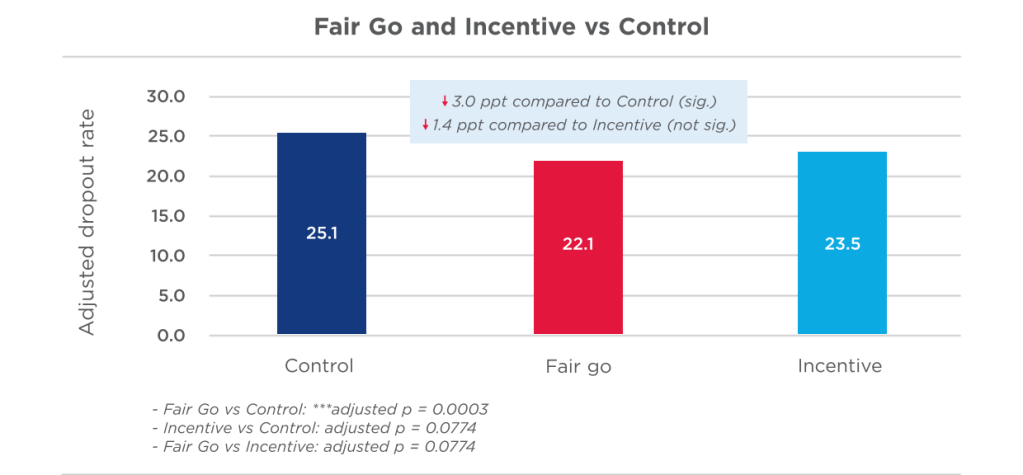

When we tested effectiveness of the two messages, the Fair Go message significantly reduced

the dropout rate by 2.8 ppt in comparison to the Control group (who did not receive any

SMS), and by 1.6 ppt compared to the Incentives group. The Incentives message reduced the

dropout rate by 1.2 ppt in comparison to the Control group, but this was not statistically

significant.

Our low-cost intervention led to $2.0M avoided costs for NSW Government and a further $1.1M avoided costs for business. For 2020-2025, the net present value is $2.4M.

Economic analysis shows the messages offer a sevenfold return on investment. This means that for every $1 the NSW Government spent on supporting learners in this way, $7 is returned in benefits, primarily of students progressing with their qualifications, as well as other benefits to businesses.

Scaling

After completing the trial, I created a scaling pack for our partners, so they could send the messages without my help.

The pack provides practical advice on how to construct messages, considerations for testing the timing of messages, and how to evaluate effectiveness of messages. The pack included advice on how to:

- Create a database of learner contacts: our trial found that some of the contact details that students use to sign up for their courses quickly becomes out of date and requires updating. Without our trial, our partners did not know how to identify these lost contacts, because they otherwise rely on students to manually update their details.

- Coordinate action across regions. When students respond to SMS messages, our partners can relay requests to the correct local office, who can then respond to the students’ requests.

- Manage, measure and report on the effectiveness of SMS messages. I trained our partners on how to use a messaging platform to schedule messages, and how to use analytics to track responses for each SMS campaign.

Our partner has used these methods and insights to maintain contact with new learners each year, and test new messages.

Our messages are now sent routinely to all first-year apprentices and trainees across New South Wales.

How Social Science Helped

- Behavioural science principles were used to design and test effective messages

- Behavioural science methods were used to identify knowledge gaps in the organisation, to improve services (e.g. updating contact records), and to optimise the customer experience of students needing help

By implementing our scaling guide, our partner was able to:

- Establish and sustain positive contact with students

- Offer improved services and support, and encourage student commitment

- Reach their customers at strategic times when learners are most vulnerable to cancelling their contracts

- Continue measuring the impact of messages through behavioural science and analytics to improve results over time.