Social science can be used to encourage employers to follow workplace regulations. This post covers how to increase compliance by appealing to social norms, providing practical examples of how to implement new requirements, and by sending timely messages that encourage change.

Summary

- An agency wanted to encourage employers to comply with supervision requirements of apprentices and trainees

- Students suffer because the status quo is to treat apprentices and trainees as workers rather than as students who need guidance on-the-job

- Research shows that simply providing information about rules and penalties is not effective in improving compliance

- Regulations about supervision are often hard to understand and difficult to follow

- Giving employers information in plain English, with examples on how to follow the rules, makes it easier to change behaviour

- Showing examples of what good supervision looks like is effective in creating change, such as how to talk about safety with apprentices

- Other practical tips about what to do, when, and how also helps, such as the ‘Happy Sad Happy’ technique for constructive feedback

- Sending employers timely supervision tips at 12pm on Wednesdays has proven effective in retaining students.

Background

I worked with a vocational education and training agency (‘VET Agency’) seeking to increase compliance with workplace requirements for supervising apprentices and trainees. Legislation can fine or ban workplaces that provide inadequate supervision of apprentices.

VET Agency was preparing a communication campaign to inform employers about the fines, in an attempt to improve supervision standards. Social science research shows that information alone is not enough to change behaviour, as people need additional assistance to implement change.

Moreover, penalties are not always effective in changing complex behaviours. People also perceive that penalties make things worse for those who are already disadvantaged.

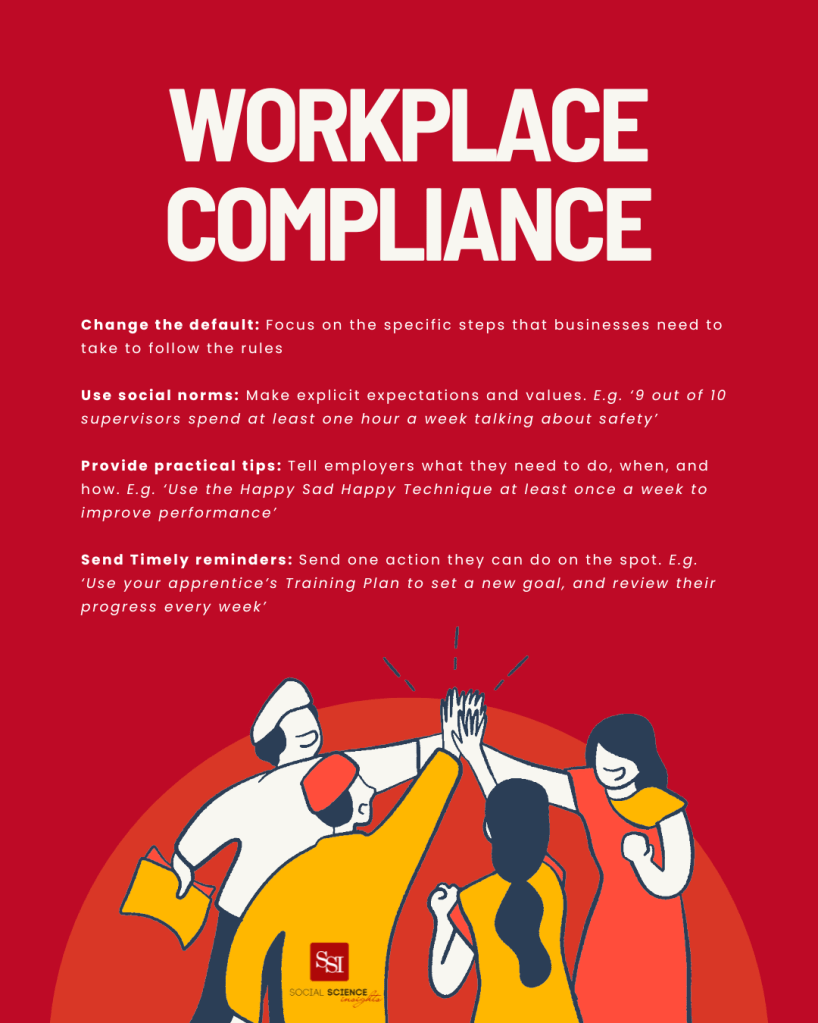

Changing the default

Regulators, including government, often communicate rules in an overly complicated way. They often give important information in legal speak, which is hard to follow. Research shows that people aren’t able to retain and sort through dense information, leading us to be ‘unable to make a decision or to stay informed on a topic’ (information overload).

One of the behavioural biases impacting business compliance with new legislation is status quo bias. This term describes how people will resist change and always go with the set option — the status quo — because it is easier to follow what is already in place.

Many people who take on apprentices and trainees are sole traders and small businesses. They don’t always have the time, resources, and knowledge to follow best practice, and so they may struggle understanding new laws and requirements. They often do not have a human resources department to help them implement new guidelines, and finding this information may seem too hard. So, they keep doing what they have always done in the past.

Businesses hire apprentices and trainees to fill in increased work load and labour shortages. In blue-collar settings, employers ‘view students as labour, rather than employees in training,’ leading to an inadequate on-the-job training experience. There are also discrepencies between the skills employers seek versus the requirements of formal qualifications. In these cases, employers may be less motivated to support their learners to complete their qualifications, as these students are already working for them ‘on the books,’ so they may not see the point in supporting further study. In this case, these employers see little business value investing in additional external training.

Only 42% of students who drop out of their qualifications are satisfied with their employment experience incomparison to more the majority who complete their qualifications (80%). Three-quarters of completers are satisfied with their supervision on the job, in comparison to half of those who quit (53%). In order to stop students dropping out, ‘New apprentices must be constantly supervised and monitored in the first 100 days.’ The supervision experience is pivotal to keeping students engaged, rather than their formal vocational training.

To help change the default on poor supervision, we need to make it easy to understand the rules. I provided advice to VET Agency on how to:

- Simplify the information using Plain English

- Focus on the specific steps that businesses need to take to follow the rules. Use bullet points of five points or less to communicate key changes

Using social norms

Many employers have been apprentices and trainees themselves. Research shows that some employers believe that current-day students are less committed than they were at their age. With this mindset, they leave apprentices and trainees unsupervised, because they think students need to ‘tough it out’ to become stronger workers. This is not necessarily the case. Individuals, especially those in power, often discount the adversities they overcame in the past.

We tend to see other people’s actions as a result of their character or personality, while we see our own faults and failures as the result of external factors beyond our control (fundamental attribution error). We perceive our individual success as the outcome of our personal effort, but our failures are blamed on other forces. We cut ourselves a break, while holding others to a higher standard. Employers may think that apprentices and trainees don’t succeed because they aren’t good enough, however, they may not have set clear expectations, while also forgetting how much they struggled in their first year, and the help they had along the way.

A better way to improve behaviour is to use social norms. That is, to make explicit the expectations and values that other people follow.

I showed VET Agency how to demonstrate to employers that helping their apprentices and trainees is more common than letting them struggle, using this simple social norm message:

‘9 out of 10 supervisors spend at least one hour on the job talking about safety with their apprentices.’

Practical change

You can also provide employers with practical tips for how to change their behaviour. The aim is to change cultural attitudes, because otherwise some employers don’t know any better. For example, many employers do not know what’s required of them as supervisors, from induction to mentorship. They do not always understand that they are legally required to provide a minimum of three paid hours per week for their apprentices and trainees to attend formal training.

To encourage compliance with supervision guidelines, it is best to tell employers what they need to do, when and how. For example:

“Effective supervision means working side by side with your apprentice during the day, and providing positive and constructive feedback. Use the three-step ‘Happy Sad Happy’ Technique at least once a week to improve your apprentice’s performance. Give them praise for what they’re doing right, followed by corrective feedback on how they can improve, and finish with more praise.”

Timely reminders

Think about the timeliness of your messages. My previous research shows that messages are most effective at 12 pm, or over lunch, on Wednesdays.

The next best times to send messages are at 11 am and at 3 pm.

Organisations might consider sending businesses one action that they can do on the spot as soon as they receive a message. It needs to be quick and easy. For example:

You cannot assume your trainee knows exactly how you would like them to behave. Set a new goal today and then review their progress at the same time each week. You can use their Training Plan as a guide.

By sending simple and practical tips, you can change behaviour over time, rather than presuming new laws and penalties will undo years’ worth of ingrained habits.