‘Race at Work Within Social Policy,’ has been published in the book, Critical Racial and Decolonial Literacies: Breaking the Silence, edited by Dr Debbie Bargallie and Dr Nilmini Fernando. This book chapter demonstrates how inadequate racial literacy impacts social policy documentation, including policies attempting to implement anti-racism principles.

Three case studies illustrate how white supremacy prevails: in a state strategy aimed at advancing Indigenous data sovereignty, policy meant to enhance service delivery for First Nations people, and an action plan seeking to increase disability inclusion in the public service.

I explore how lack of racial literacy maintains what I term hegemonic diversity. That is, focusing on individualistic approaches to policy and practice, such as ‘celebrating’ individual differences, without dismantling racism and other structural inequities. I show how a racial literacy framework can enhance social policy.

Read an excerpt below.

Excerpt: Racial literacy in practice

Research indicates that the Australian public service more broadly has made little progress in addressing institutional racial justice; glaringly few staff and senior leaders are Indigenous (Bargallie, 2020: 65) and from migrant, non- English- speaking backgrounds (Opare- Addo and Bertone, 2021: 9–11). Race, gender and class inequalities are institutionally reproduced in the public service sector through formal practices (such as policies, recruitment and management) and informal interactions, such as when minorities are sanctioned for speaking up about unfair treatment (see Bargallie et al, 2023). However, the main driver of policy advice is written documents.

Why documents matter

Organizations measure institutional change through the creation of documents; these documents are not static, but rather move as entities through organizations and are worked on by many people from different departments (Ahmed, 2012: 85). Policies become enacted only after they are documented, but before this there are conversations, meetings and numerous associated activities to decide timeframes, what actions need to be taken, how to monitor progress and how success will be evaluated. Decisions are made about how to write the document – definitions of a problem, what content is included, solutions and recommendations. Documents also assign roles and responsibilities of individuals in charge of making the policy work, who holds authority and networks who have input (such as working groups).

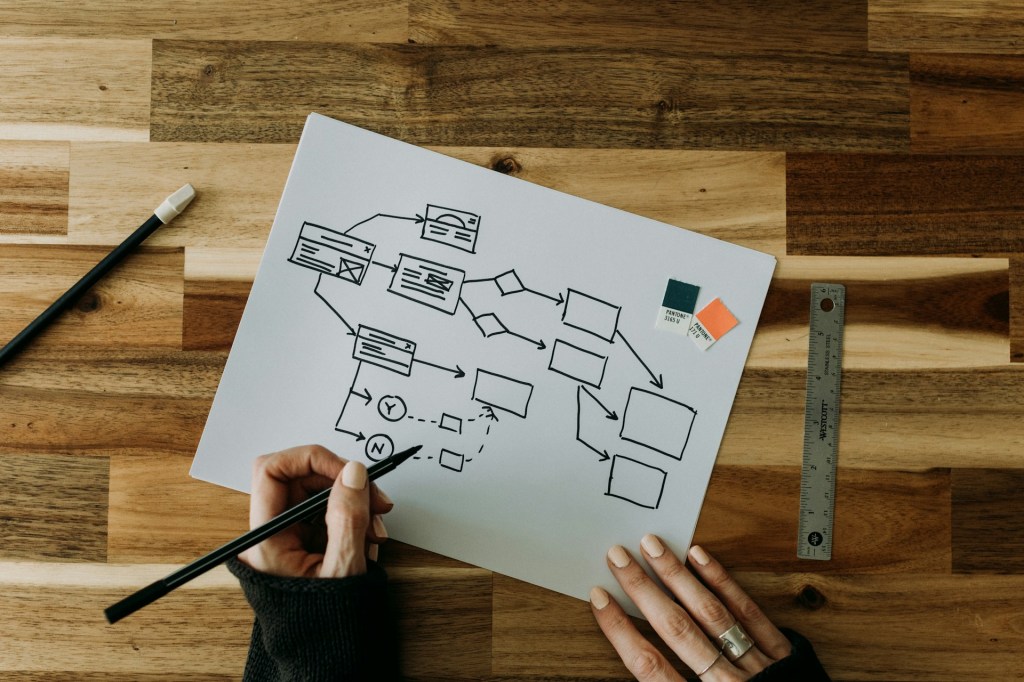

The policy document cycle is shown in Figure 16.1.

Consultation with experts is a requirement when producing policies, including diversity responses (Ahmed, 2012: 93– 4). Figure 16.1 illustrates the process for policy document creation. This is typically triggered by an external event, such as responding to a state priority, legislation, an inquiry, programme or other initiative. One team will lead the response. Documents flow back and forth as relevant agencies negotiate the content. In Stage 6 (Draft) and Stage 8 (Consult) of the policy document cycle, advice to other agencies can be provided in written form, such as responses to ministerial briefs, draft reports, PowerPoint slides and oral presentations. Deadlines for departmental and expert input are short – typically between 24 hours and one week – and senior managers are often asked to provide verbal advice on policies and initiatives without prior planning, often in face- to- face meetings. In either case, we don’t always see the outcome. This dynamic operating environment means that policy workers rely on existing expertise. At each stage, if race is not explicitly addressed, the document and subsequent policy actions reinforce the racial hierarchy by prioritizing white interests and ignoring racial justice.

Racial literacy is low in the public service (Bargallie, 2020: 14, 75, 199, 202). This means that policies rarely have race relations at front of mind. Even when anti- racism advice is provided, actions are managed by teams who have insufficient racial literacy, leading to sub- optimal results.

The following case studies show the importance not just of applying racial literacy, but of resourcing and managing these efforts correctly. The first examines racial literacy advice provided on a data strategy and an Indigenous data sovereignty project.

Read more: Critical Racial and Decolonial Literacies: Breaking the Silence.