This post provides tips for improving public health communications. I show examples from studies that encouraged doctors to comply with health guidelines. I discuss a case study of a health organisation that sought to increase patient referrals to a free treatment program.

Summary

- Programs over-estimate how much information people need to change their behaviour

- Studies show that doctors are more likely to comply with instructions if they are shown how their behaviour compares to their peers

- Requests need to be easy to read, and the personal benefits immediately clear

- I provide a health case study, showing that doctors are more likely to respond to short requests that makes it easy to refer patients to free services

- Start with a clear call to action: what do they need to do, how, and when

- Include only essential information that will help the person complete the task

- Make it easy for people to complete the action on the spot

- Use a behavioural prompt to motivate behavioural change. For example, appeal to social influence. Emails should be signed off by an influential person (messenger effect) and include peer comparisons (relative ranking)

- In the case of health professionals, show how the patients’ outcomes will be enhanced by the doctors’ actions (internal motivations)

Background

A organisation, whom we’ll call Your Health, got in touch to improve general practitioners’ (GP) referrals to their Hepatitis C treatment program.

Hepatitis ‘is an infection of the liver that causes inflammation and damage.’ Hepatitis Australia President says patients do not want to approach their doctors for treatment due to social stigma about the infection. In Australia, 300,000 people have been diagnosed, and 1,000 people die from Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C annually, but many more are undiagnosed. If untreated, Hepatitis can be fatal. Hepatitis Australia says, ‘Early detection is crucial.’

New treatments have a high success rate. For example, a trial of over 700 people with Hepatitis C finds that early detection of genotype 1 (a genetically distinct group of Hepatitis C virus) leads to a seven in 10 chance of clearing the infection. However, various surveys in Australia, USA, and globally find that physicians want to support Hepatitis patients, but they lack adequate knowledge of novel therapies and new treatments. Lack of time to gain further training on best practice is also a barrier. Patients are open to being notified about available treatments, but these systems are under-utilised.

Your Health had sent GPs an email with an attached letter providing further information about their new Hepatitis services, but had received little response.

Whether we’re asking people to consider a service that would improve their wellbeing, or to donate to a great cause, or offering a free social program — people are often put off responding if we give them too much information.

My previous research shows that communications about health programs are often dense, and sign-up processes are difficult.

Many organisations assume that people need lots of information in order to be convinced to take action. Our research shows that, even in health settings, sticking to short messages with a call to action and clear instructions is more effective than lengthy communications. We provided patients in health clinics an A5 postcard about how to correctly self-isolate after a COVID test. This reduced the number of people leaving home before they had a negative result by 23%. We provided an optional QR code for those who wanted more information, but only 11% of people read the webpage, with the majority leaving within four seconds. This suggests extra information is not needed to comply with health directions.

Research shows that short communications can get general practitioners to change their behaviour, in comparison to longer emails with dense information.

Example 1: A UK study sent 800 GPs a short letter from the Chief Medical Officer, asking them to stop over-prescribing antibiotic medication. Those who received the letter reduced their prescription rates by 3.3% compared to those who didn’t get the letter. This led to 73,406 fewer antibiotic prescriptions, and savings of £92,356. The message appealed to peer comparison. It said:

‘The great majority (80%) of practices in [Your Local Area] prescribe fewer antibiotics per head than yours.’

Michael Hallsworth, et. al. (2016), The Lancet

Example 2: An Australian study involving 6,649 GPs finds that those who receive a short letter with information about how they compare with their peers similarly reduced over-prescription of antibiotics. The peer comparison letters that included a comparison graph resulted in 12.3% reduction in prescription rates over six months. An education-only letter that described the harms of overprescription reduced prescriptions by 3.2%. The study led to 126,352 fewer scripts over six-months. This message similarly used a peer comparison.

‘Dear [Dr Name], you prescribe more antibiotics than 92% of prescribers in your region.’

BETA (2018)

What we did

Your Health seeks to reduce the rate of Hepatitis C. The organisation runs a free treatment program. This is a key Government initiative. Your Health has emailed 80 general practitioners (GPs) around the state who have eligible patients, but only two GPs had referred their patients to the program.

The email explains the program, its background, statistics on Hepatitis C, and it ends with a request for the GPs to make a referral. The email is signed by the program manager, a senior, highly qualified, registered nurse. The email includes an attached two-page letter with more information about the program and a form to make the referral. The letter must be printed, filled in and signed, scanned, and emailed back to the nurse.

Your Health has sent the program manager to visit GPs, but this has not improved outcomes.

I took Your Health through a rapid assessment using a behavioural journey map, to understand the context in which GPs work.

How we did it

I analysed the Your Health email and letter, and their referral process.

My analysis shows that:

- The email lacks urgency. The email does not provide a due date for the referral. People will not prioritise action if it does not seem urgent

- The email and letter do not clearly communicate the program’s benefits to patients, the eligibility criteria, and GP requirements

- Health practitioners are more likely to prioritise change when they are told how their patients will be impacted (internal motivations). For example, a simple reminder, such as a sign saying, ‘Hand hygiene prevents patients from catching diseases,’ increased the use of soap and hand-sanitising gel in hospitals by 45%, as well as a 10% improvement in hand-hygiene among health care professionals before and after contact with patients

- We need to eliminate ambiguity about what’s expected of the GP after the referral. Your Health’s service incurs no further costs and time to the GP, but this is not clear

- Emails are screened by the GP’s administrative managers. They are information gatekeepers who make a decision about which emails are urgent and valuable, and whether or not to forward the email to the GP to read. The sign-up process therefore needs to be easier for administrative managers to make this assessment

- There are too many steps in the referral process. The GP (or more likely, the admin team) would need to print out the letter, fill it out, scan it, and send it back on behalf of the GP

- The program manager faces professional stigma. Medicine is rife with gender bias. The program manager is a woman, and a nurse. Nurses sometimes lack respect from physicians, including men and women doctors. It is possible that the program manager’s requests are treated as being less urgent due to gender and professional norms.

What we found

I have previously detailed how to use behavioural science evidence to condense essential information. I provided Your Health the following advice on how to make the referral process more effective.

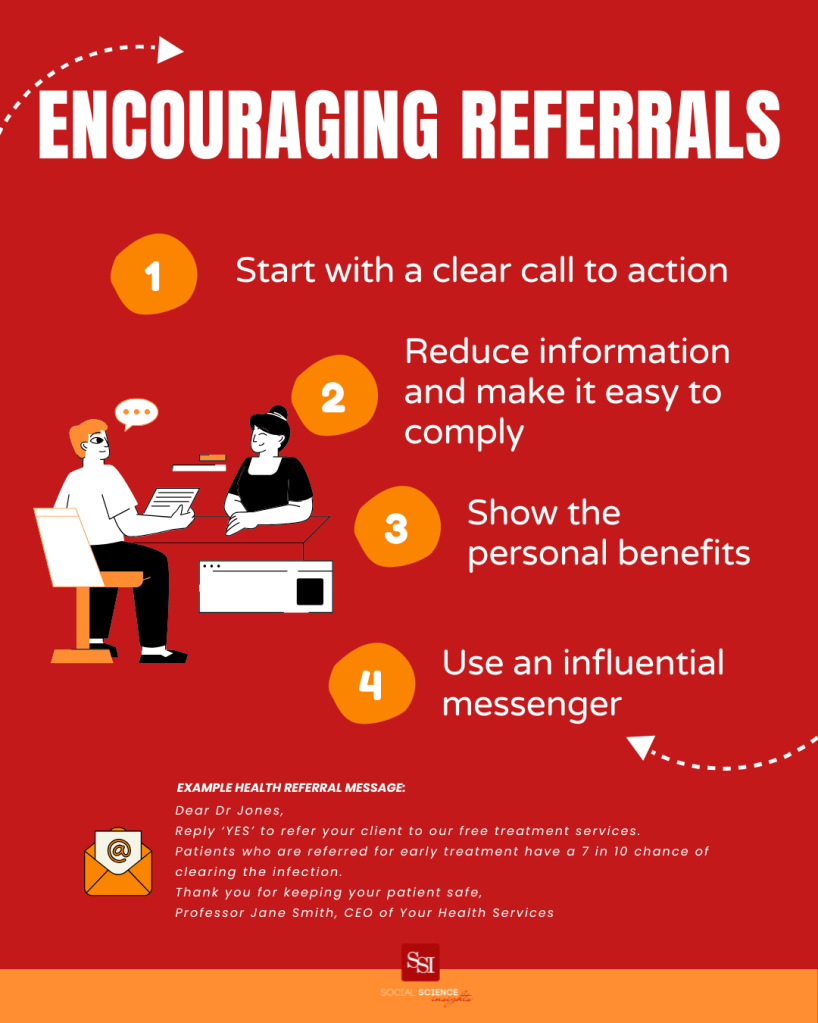

Start with a clear call to action

What do recipients need to do? How do they do it? When do they need to complete the request?

The revised email is personalised to each GP. It begins with the request to refer the patient by a specific date. The email signals the urgency by emphasising that early intervention is crucial in reducing the risk of liver cancer, and accessing life-saving care.

Reduce information and make it easy to comply

Only tell recipients essential information that will help them take action (simplification). Ensure recipients can complete the action on the spot (call to action).

The email now includes a succinct instruction to email back ‘yes,’ to authorise Your Health to contact the patient. The email notes the program is free, and that Your Health handles everything after the referral. This eliminates any fear that the GP will need to invest more time and resources.

We now include the relevant privacy and informed consent details from the letter at the end of the revised email. We remove the attachment and the extra steps from the letter.

Show the personal benefits

The email has one sentence about what the treatment involves. Your Health will provide data about why early referral improves patients’ outcomes.

Use an influential messenger to encourage behaviour change

The email includes peer comparison, by demonstrating how doctors who make the referrals improve their patients’ outcome. Your Health will use their own data about their services. An example of data from the literature is: ‘Patients with Hepatitis C who are referred for early treatment by Australian GPs have a 7 in 10 chance of clearing the infection.’

The email will be sent and signed off from the head of Your Health, a senior doctor (messenger effect). The nurse remains the named contact person as program manager and the key contact for patients and doctors seeking further information.

Example message:

Dear Dr Jones,

Reply ‘YES’ by 30 August to refer your client to our free Hepatitis C treatment services.

We handle everything after your referral. There is no cost to you or your patient.

Early intervention is crucial in reducing the risk of liver cancer, and accessing life-saving care. Patients who are referred for early treatment by Australian GPs have a 7 in 10 chance of clearing the infection.

Thank you for keeping your patient safe,

Professor Jane Smith, CEO of Your Health Services