Our research shows that apprentices who cancel their employment contracts do so because they lack support at work. They are subjected to tough working conditions for little pay. They are given menial, repetitive tasks. They work long hours. They receive little guidance about their progress on the job. How can behavioural science help?

The following post summarises my team’s recent report.

Summary

- For years, there has been a trend showing that around half of all apprentices and trainees (learners) do not complete their qualifications

- Our research shows that some employers lack adequate time, resources and skills to support their learners

- We tested a behavioural change intervention to support employers with low apprenticeship and traineeship completion rates. Training advisors met with employers and their learners to set goals and discuss their contracts. Employers and learners then received fortnightly messages via SMS to reinforce the learners’ goals. After three months, the advisors rang the employers and their learners to see how they were going

- We started our trial in November 2017. We then tracked the learners’ outcomes over 12 months. We found that many learners who cancel their contracts leave within the first three to six months of their first year. This meant that those who would have benefited most from the intervention had already cancelled by June. Without this trial, our partner organisation would not have understood this pattern

- Our interventions did not lead to statistically significant results. Learners who received our treatment were no more likely to stay in their contracts than those who did not receive additional contact from the training advisors

- Nevertheless, our analysis showed that around 20% of learners who quit their first contract will keep studying

- Our methods revealed a lag in cancellation or non-completion records and identified numerous ways to improve customer service through enhanced data collection and technology

- We suggest that behaviourally informed support in the first 12 months can help learners persevere toward completion

- We are now testing this idea through a new trial that is already showing positive results.

- Social science helps organisations understand employment patterns and test a solution to a workplace problem. Testing can unearth unknown workflow and systemic issues that hinder customer outcomes

- Using behavioural science, organisations can improve their processes and strategic objectives. In this case, understanding when students are dropping out and providing support earlier.

Background

Completion rates for apprenticeships and traineeships have remained steadily low for years. In 2015, the New South Wales Premier set a State Priority to increase apprenticeship and traineeship completion from 50% to 65%.

In 2010, the cost of New South Wales trade apprenticeship non-completion to the state and federal governments was $91 million, and the total cost of non-completion including productivity forgone plus budgetary impacts was $348 million.

Longterm data indicates that the overall completion rate is stable and potentially hard to shift.

What We Did

Our team partnered with Training Services New South Wales (TSNSW) to support employers with low apprenticeship and traineeship completion rates. Training Services is the regulator of apprenticeships and traineeships in New South Wales.

My colleagues undertook a literature review and fieldwork, as well as scoping and designing the intervention. I led the analysis phase and scale-up.

My colleagues conducted 50 fieldwork interviews with learners, employers, registered training organisations (including TAFE NSW), and other stakeholders. This showed two key barriers to completions: lack of employer support and a significant disconnect between study and work.

Lack of employer support

Employers with high completion rates nurture and encourage their learners. They value their education, show them leniency when they make mistakes, and see apprentices as the future of their business. For example, one employer said:

‘We couldn’t run without apprentices. I don’t think they know how valuable they are. I’m upset when I hear that they think that they are just cheap labour. I’m entrusting them to work on cars over $100,000 in value, I wouldn’t take that risk if I thought they were just cheap labour.’

These employers:

- Provide formal and informal feedback

- Know what their learners are doing at their training organisation and connect this to their on-the-job training

- Hold tool box talks as a safe and open way for apprentices to communicate

- Assign mentors

- Support on-the-job training while progressingly signing off on workplace competencies.

While some employers strongly support their learners, other employers lack the time, resources or skills to effectively supervise and mentor learners, leading to demotivation and lower completions.

Our fieldwork showed that employers with low completions are:

- Time poor: job is demanding and their learners are not their top priority

- Don’t value formal training delivered by training organisations

- Disconnected from their apprentices’ experience. E.g. They have forgotten how hard it was like to be an apprentice

- Don’t know best practice

- Face structural barriers: lack funding, capacity, and infrastructure to implement best practice.

These employers take little responsibility for their learners’ poor outcomes:

‘Apprentices have an easy time compared to when I did my apprenticeship.’

‘These apprentices aren’t as smart.’

‘These apprentices are irresponsible and immature – they aren’t grateful for the chance I’m giving them’

‘What they learn there [at their registered training organisation] is important, but not as useful or important as what we are actually doing at work.’

Our fieldwork finds that employers have the most influence over their learners’ outcomes. Employers with low completion rates see the issue lies with the student, rather than their work context. Training organisations, apprenticeship support network representatives, and learners feel unable to intervene.

‘I do what I can to keep the apprentice, but they just don’t stick it out, so I have to keep on getting new apprentices.’ (Employer)

‘If I want this qualification I just have to accept everything the way it is. If I complain or call my boss out, then I’m just going to lose my job, or make the situation worse.’ (Apprentice)

Learners spend 86% of their time in the workplace (the other 14% at their registered training organisation, such as TAFE). For apprentices who complete their qualifications, good supervision was essential:

‘If I didn’t know what to do I would just ask my boss. She is a good teacher and really understanding’

‘My relationship with my boss was good, if I didn’t know something he would show me and I would do it. I could also ask the other chefs. We are close mates, you can’t avoid people in a kitchen.’

These learners say work was hard, but manageable, when they felt like they were learning on-the-job:

‘The first year was really full on, I got yelled at a lot, it was a learning curve, but you just keep improving.’

Employers with low completion rates tend to be reluctant to invest time and training for their learners. This lessens the opportunity for the learners to apply the skills that they have learnt at work.

For those apprentices who cancelled, they stuck it out for as long as possible, until they ‘broke’:

‘My boss would speak to me like I was garbage… he would always yell at me about the same thing over and over. When I left after one year, I was the longest serving employee to ever work there.’

‘I liked the work, but I was always pushed to do more and more. For the first few weeks I was on the shovel, and you get tired very quickly when you aren’t used to it… it’s real hard yakka work. Other apprentices did similar work, but their bosses were better. I felt like I was killing myself at work. Other employees at work were doing similar things, but I was put under more pressure to work faster than others. It really depended on what foreman I was working under at a site. I was always put with the worst foreman… I had to keep my mouth shut unless I was spoken to … it was hard to fit in.’

Learners who struggle in an unsupportive workplace say that they often feel they are subjected to tough working conditions for little pay. They are given menial, repetitive tasks and they work long hours. They receive little guidance about their progress on the job. Typical comments from learners from our fieldwork include:

‘At the end of the week, I’m working as hard as I can to walk away with nothing’

‘I’m not getting any training [at my paid job]’

‘My boss/ supervisor makes me feel worthless and is waiting for me to fail’

‘Being at TAFE is my chance to mix with peers and be in a place where I’m not at the bottom of the food chain. I’m with equals and feel more myself and more respected.’ (Emphasis added)

Significant disconnect between study at TAFE and what happens at work

At work, learners often do not communicate what they are learning to their employers. Consequently, employers do not value the training their learners received at TAFE, and do not give them a chance to practise new skills.

‘There is a tension between the TAFE learned skills and the actual applied skills in the job.’ (Group training organisation)

Learners become overwhelmed, and don’t know where to get help. So, they end up quitting. Our trial went on to show that these learners tend not to advise TAFE nor TSNSW when they drop out, so these organisations don’t know when their learners leave.

To address these issues employer support and training disconnect, my colleagues co-designed an intervention with TSNSW to support employers with low apprenticeship and traineeship completion rates. This included:

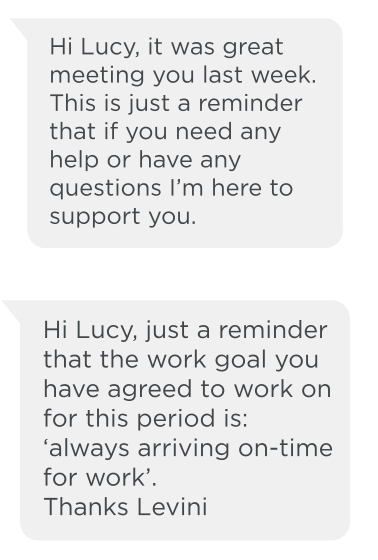

- a face-to-face meeting between TSNSW Advisors, learners and their supervisors to set goals and discuss commitment to contractual obligations

- fortnightly messages to employers and their learners to reinforce these aims

- a follow up phone call after three months to check on progress.

How We Did It

My colleagues ran a randomised control trial to test whether expanding support offered by training advisers (TAs) to apprentices and trainees (learners) with employers with historically low completion rates could improve completion rates. We hypothesised that this employer support would then increase the rate at which the learners completed their apprenticeships or traineeships.

We focused on employers with low rates of completion over the past five years (below 42% completion; the NSW state average at the time being 47%).

We started with a sample of 343 employers which (along with their 2,229 learners) were randomised into two groups (treatment and control). Four months later we added 273 learners that had started working with the employers since the trial started.

There were 1,975 learners in the final analysis, once we excluded learners who had cancelled their contract or completed their study before the trial started. That is, once we undertook our analysis, we realised that we had lost around 20% of our sample by the time treatment began). As this trial was randomly allocated, we could not have known about this attrition without having done this trial.

Treatment (n = 906)

These employers and learners received an expansion of support offered by TAs, including:

- One site visit from a TA to see all the supervisors and learners (to review contractual responsibilities and establish agreed-upon goals for learners).

- Fortnightly communications for a period of three months encouraging them to persevere with the learners’ goals and their mutual contractual obligations (text messages from the TA to the learner, and fortnightly emails from the TA to the learner’s supervisor).

- A final phone call three months after the site visit, to check on progress on the learners’ goals, and troubleshoot any issues.

Control (n = 1,069): Business-as-usual

This included help already available to learners and employers who proactively request support, but no additional site visits, texts, emails or phone calls.

What We Found

Our intervention had no impact on whether a learner stayed in a contract or completed their study during the contract.

Our primary measure was the 12-month retention rate of learners. We followed learners’ outcomes by tracing the first contract they had already started at the time our trial began in November 2017.

Our intervention had no impact on employer performance. Looking at the level of the employer, for the control group, 62% of their learners had either completed or were still studying, compared to 60.5% of learners in treatment.

Around one-fifth of learners who cancel a contract will go on to start a new contract

A cancelled contract is not the end of a learner’s journey, as 16.3% of learners in the treatment group went on to start a new contract after cancelling their first (and 15.9% of learners in the control group did the same).

Our trial methodology identified data and service delivery issues that may have impacted our results.

- Learners who cancel their contracts tend to leave within the first three to six months of their first year. Our intervention started in November, meaning those who would have benefited most from the intervention had already cancelled by June. Without this trial,

we could not have identified this issue of timeliness of support. - To reach optimum sample size to achieve statistical power, we included learners

from first to third year. Given our trial subsequently identified most learners who

cancel will do so in their first year, our sample is capturing a range of behaviours

for learners at different stages.

TSNSW endorsed our trial recommendations, which included:

- sending timely messages within the first six months of the first year

- enhancing processes using technology, including improved data collection,

analysis and auditing of cancelled contracts.

Next Steps

In line with our recommendations, in February 2019 we began testing a SMS intervention to encourage learners to proactively seek information and support when they encounter issues, instead of simply dropping out. This trial includes all first-year apprentices and trainees in NSW (n=13,100) based on the insight that learners tend to cancel in their first year without seeking help or notifying Training Services NSW.

Interim results

For this trial, we are measuring completion rates as our primary outcome. Whilst final data is not yet available, we have found encouraging short-term engagement results.

Two intervention groups are receiving messages with links to existing online resources on the TSNSW website as well as the option to call their local TSNSW office for further support (n=8,500). The Control group (4,600) receives business-as-usual, which means no text messages, but they have the same access to the online resources and ability to phone the local office for support.

In the first half of 2019, we sent the two intervention groups three messages. This led to 4,400 clicks on links onto the TSNSW website for information on workplace rights and financial entitlements, plus almost 400 phone calls and a further 400 inbound text messages seeking help. The texts prompted students to tell TSNSW about a range of issues they would otherwise not have, such as unfair dismissal, lack of action on their learning plan, and financial assistance.

We continued to message learners until the end of 2019 (a further three text messages) and are subsequently testing whether this engagement translates into completions.

How Social Science Helped

- Social science theory helped my colleagues to identify national and international patterns in completion rates and solutions that had worked in other settings

- Social science methods helped my colleagues narrow down a solution from the academic literature that was worthwhile testing in the New South Wales context

- Social science rigour led to new insights. While our solution did not have a statistically significant result, testing a solution unearthed many workflow and systemic issues that our trial partners had not previously evidenced. This includes issues with their data and information. For example, they have a gap in identifying students who are most at-risk of dropping out of their contracts. Our analysis also showed when attrition is most likely to occur (within the first three to six months). This allowed our partner organisation to learn from our trial

- Social science training through real-world solutions. I am working with our partners to test another solution that builds on the lessons from this previous trial. Social science helps our partner to fulfil its strategic objective to be a learning organisation who is at the cutting edge of using technology and innovation to better support its learners

Notes

Our results were first published in our report. I have added further background context and the section on social science above.