This social science project identified what stops people from voluntarily signing up to free rehabilitation programs. These results may help other community programs to improve their services.

Summary

- Our partner is a justice agency seeking to improve the number of people signing up to voluntary rehabilitation programs

- I conducted fieldwork across New South Wales with clients and service providers working in mental health, domestic and family violence, and alcohol and other drug rehabilitation

- We found that many voluntary programs have hidden barriers that make signing up difficult and unappealing (friction costs)

- Programs can make it easier to sign-up, by reducing the number of steps, and simplifying referrals and eligibility requirements

- Programs can also make joining more appealing by personalising offers and making the immediate benefits clear

- Clients are most open to join new programs in the first 24 to 48 hours following their release from prison (fresh start effect)

Background

The following post summarises my team’s recent report.

The New South Wales Government has committed to reducing adult reoffending by five percent, by 2019. Reoffending refers to individuals who have been repeatedly charged and convicted of a criminal offence.

Twenty-three percent (23%) of adults exiting prison in NSW go on to be re-convicted within 12 months, and 56% of adult ex-prisoners will be re-convicted of another crime within 10 years.

What We Did

Our partner agency wanted to increase recruitment and sign-up of voluntary, criminogenic programs. That is, programs addressing behaviour change, such as domestic and family violence behaviour reform, alcohol and other drug rehabilitation, anger management, mental health counselling, and other health services.

Our partner wanted to know why people aren’t taking up free services, how this might vary across regions, and how to address client recruitment issues.

How We Did It

I conducted desktop research about the motivation and commitment requirements that impact people’s decisions to join new programs.

I interviewed 46 clients and experts about their experiences in voluntary programs. I also conducted site visits with service providers across metro and rural New South Wales.

- Thirty-five service providers: from the justice sector (solicitors, magistrates, restorative justice specialists, and prisoner advocacy workers); the health sector (alcohol and other drug counsellors, and mental health professionals); Aboriginal community-controlled organisations; and other not-for-profit service providers

- Two academic experts: provided insights on recidivism, crime prevention, and correctional justice

- Nine clients: currently in voluntary programs, living in the community whilst awaiting sentencing. They are participating in service delivery programs targeting criminogenic issues

- Five site visits: ethnographic research with service providers. I spoke with managers and staff about their services and, with consent, observed their interactions with clients.

What We Found

My fieldwork found that sign-up processes are cumbersome and off-putting, often requiring people to reshare their criminal history. Screening tools are often invasive and scary.

Clients have a hard time distinguishing services and trusting new programs, due to their past history where they were treated unfairly.

Clients feel they are set up to fail, due to strict requirements to demonstrate that they’ve changed very swiftly.

Case workers find it difficult to follow best practice, especially in times of high stress.

There are many implementation barriers that prevent recruitment and retention of clients. For example, clients lose eligibility for services if they have to go back to court. The reality of reoffending patterns is that people released from prison are often facing multiple court appearances, and they don’t get a chance to make progress in between.

My fieldwork informed recommendations to improve recruitment in voluntary programs.

Making behaviour change easy

Our fieldwork suggests that reducing the barriers and difficulty of taking up services (or ‘friction costs’) is the most effective way to establish engagement with clients. Appealing to the novelty of programs and simplifying choices also helps.

Simplify eligibility processes. Use pre-filled forms that can be swiftly completed on the spot. Ideally, this might be done on a tablet or another portable electronic device that reduces manual entry.

Use default settings. Streamline processes, to enable providers to seek informed consent from clients as soon as they agree to participate in a program. This will enable providers to more easily and transparently make enquires about clients to other agencies. Clients opt-out rather than opt in as a default.

Reduce hassle for clients. Negotiate meetings to make case management easy, for example, case managers might meet client in convenient places. Providers might develop a process to minimise or combine appointments in liaison with other agencies

Making joining attractive

Programs can increase engagement by making services more appealing. For example, using personalised communication, highlighting the benefits of the program with a clear call to action, and address perceived risks to clients.

Address salience using a script. Swiftly establish the benefits of the program, while also promoting a personalised service (personalisation). Use phone and mobile messages and improve other points of engagement.

Draw attention effectively. Personalise messages to draw attention to services. Highlight benefits through design of communication materials (such as enhanced letters and marketing).

Make joining appealing. Show why clients are being encouraged to join a specific program and how it’s relevant to their current predicament. Clients say good programs and case workers help “keep you on track,” “help you stay healthy,” and help them stay out of jail.

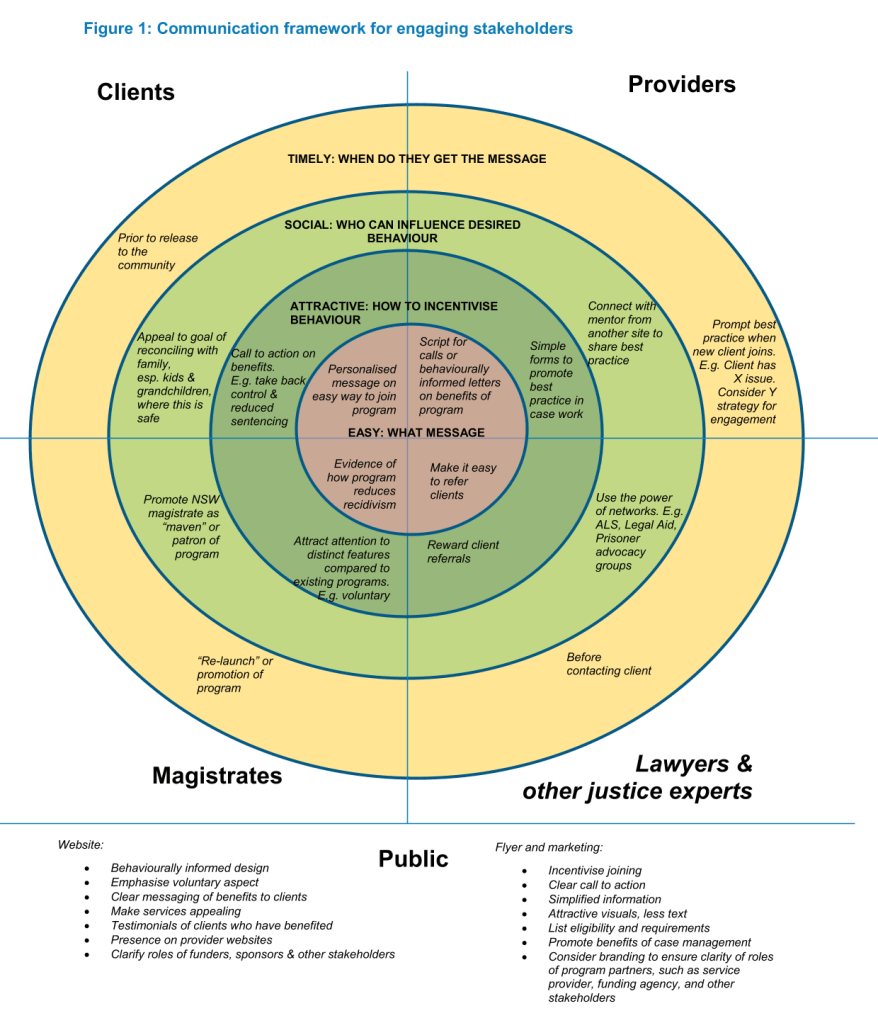

The diagram below highlights how to make messages more attractive for clients as well as stakeholders.

Harnessing the power of social norms

Programs can reduce the stigma of signing up, by drawing on a behaviourally-informed screening tool to assist case management. Screening questions might be reduced and simplified, to focus on patterns of behaviour, and in turn, inform goal-setting and commitment to family and friends.

- Draw on a limited number of questions

- Use a simplified template

- Use checklists

- Use visual feedback about patterns of behavioural, short-term goals and program outcomes.

- Make personalised recommendations that the client immediately understands.

Use the screening tool to prompt best practice from case workers and to enhance clients’ self-esteem at the point of assessment.

Encourage commitment. At the end of the assessment session, the tool might provide a meaningful measure that could be provided to the client as a type of commitment device. This could be writing down a goal that emerges from the assessment. Behavioural science shows that making commitments to family or friends increases the likelihood of achieving goals.

Use social norms. Mainstream programs do not meet the cultural and spiritual needs of minority clients. Consider culturally-relevant questions and measures that are meaningful to specific culturally and linguistically diverse groups.

Making a timely offer

Offer programs at the optimum time when clients are open to change. Clients and service providers say the best time to approach clients is at a moment of reflection, when they are fed up with the cycle of being reimprisoned.

The first 24 to 48 hours after being released into the community in the case of pre-sentencing is an ideal time to engage people at high-risk of reoffending.

Pre-sentencing treatments are most effective where there is no delay between trial and treatment.

Discuss the client’s desire to reconnect with family (especially children and grandchildren),

where this is safe.

Leverage SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound). In a typical 12-week program, a series of small goals would be best. This could be to attend at least 7 out of 10 sessions with a therapist to work on a family-related goal (such as reconnecting with children or grandchildren), or to reduce (rather than eliminate) alcohol and other drug use.

Implementation factors

Clients are put-off engaging in programs by past bad experiences that have been re-traumatising. As a result, clients are wary of starting over with new programs and new case workers. This distrust is compounded by implementation barriers that make joining programs a big hassle. This includes:

- Improving avenues for contacting clients. Clients are hard to contact because they are often homeless or in precarious housing. A solution might be to contact hard-to-reach clients through trusted stakeholders (such as lawyers and prisoner advocacy networks)

- Creating easy options to engage. Programs seem inaccessible, especially when clients have limited travel options. Having mobile and flexible case workers who can drive out to clients or accompany them to appointments makes it easier to engage clients

- Keeping referral pathways open. Referral programs can be limited if they come from only one source, such as police and Community Corrections. Referrals through exiting service providers, Aboriginal community-controlled organisations, and self-referral can be more powerful levers for change

- Producing easy-to-use tools for best practice. Best practice for case management is well documented, but this is often in dense manuals that are hard to recall on day-to-day

- Facilitating collaboration. Privacy provisions of some programs can sometimes hamper cooperation between service providers, court users and criminal justice stakeholders. Some programs will have privacy restrictions that means client history is withheld from service provider. Service providers stress the importance of case history, to better understand criminogenic patterns and to pre-empt any outstanding legal issues

- Working with Magistrates to consolidate charges. Clients are sometimes unable to complete programs due to other outstanding charges, which lead them back into the court system. Negotiating a more straightforward process to combine outstanding charges and pending court cases would enable clients to maximise their opportunity to fully commit to rehabilitation

- Establishing a representative justice programs advisory board made up of Aboriginal service providers and experts from rural and metro regions. Aboriginal service providers experience consultation fatigue, with multiple programs and services seeking their input after new programs are launched. Setting up an advisory body of various Aboriginal community-controlled organisations, legal representatives, community services and elders would lift this burden from ad hoc requests. Advisory members should be remunerated adequately

- Engaging stakeholders early on aims, roles and outcomes of new programs. When new programs are launched, misconceptions can quickly spread and lead to disengagement. For example, lawyers may not have visibility of certain programs or have the ability to refer their clients into a program. This closes a potential opportunity to engage clients.

I designed this infographic to promote our findings to busy practitioners and policymakers.

How Social Science Helped

- Research methods: qualitative interviews and ethnography of community services

- Theoretical insights: our recommendations are based on best practice literature

- Systemic reforms: a social science perspective helps to put individual troubles in broader cultural context. In this case, the institutional processes that prevent clients from taking advantage of rehabilitation programs.